Critical thinking is an expression that’s been mentioned a lot for the last few years – in the workplace, education, parenting. It comes with a big fancy definition explaining various sub-skills like evaluating or synthesizing, etc.

What it actually means in more laymen terms is:

- Using your own head to think and arrive at a conclusion

- Being able to look at different perspectives

- Understanding the process of thinking

- Looking both at different parts and the whole of an issue, problem, etc.

- Understanding the cause and effect

- Thinking about solutions and potential problems of each solution (long-term vision)

We would all definitely like to raise children with these skills – not only they are useful for school or work, but also for managing daily life.

More ambitiously, they would be making a positive change in the world. When you are able to understand things on such a deep level, with all angles covered and long-term effects taken into account, a lot of the problems we are facing in the world at the moment, would have better solutions.

So, how do we teach critical thinking skills to our little ones? It is actually easier than you think.

Here are a few simple tools:

-

Don’t give them all the answers immediately.

Children ask a lot of questions, they want to know how things work, why something happened, why people behave a certain way. Instead of giving them your own view and explanation – turn the question back to them: “What do you think?” They have an opinion, trust me, even very young ones. You might get the funny or impossible answers, but you are making them spin those little mental wheels and you are also opening a door for deeper discussion.

-

Challenge their view.

When they tell you something interesting or new, ask them “How do you know?” I remember confusing my daughter by asking that question after she stated that “You mustn’t eat chocolate when you have a fever.” It turned out that her teacher said that. I kept pushing “How does the teacher know?” That really got her thinking and researching on her own. We want children to come to their own conclusions and decisions, not just taking everything they are being told for granted.

We would all like to raise children with critical thinking skills – not only are they useful for school or work, but also for managing daily life.

-

Don’t solve all of their problems.

Children are actually really smart at solving their own little problems, they might even have great ideas for the bigger ones. Your job, as a parent, is to help them look at the situation from different angles and explore the solutions and their consequences together. The final decision is theirs. So are the consequences. My dear 6-year-old student struggled with her friends. They didn’t want to play with her. When I asked her about a few ways she could solve it, she was really creative:

- Tell a teacher

- Ask mum to talk to the teacher or other mums

- Ignore them and find other friends

- Buy them presents to make them like you (I especially found this one funny and unexpected. Thinking bribe from such an early age!)

After talking about the possible consequences of each solution she decided to try to make new friends.

It is important to show children that there is always more than one way to approach something while keeping in mind the law of cause and effect.

-

Become Socrates.

Using questions, based on Socrates technique, can be quite powerful. Here are some:

- Why do you think that?

- If that …happened, how would…that be?

- Can you explain that?

- Give me an example of that.

- How can we trust that?

- How did you/he/ she come to that conclusion?

- What are you going to use to do/solve/make that?

- What will you do if things go wrong?

The basic rule here would be: listen more than you talk. Use questions to provoke deeper thinking and discussion of various possibilities. Avoid judging and labeling, encourage creativity and ideas., unless they are really dangerous.

Children are actually really smart at solving their own little problems, they might even have great ideas for the bigger ones.

-

Encourage unstructured playtime.

This might seem counter-intuitive, but when children don’t have anything planned or organized for them, their creative juices start running. Then they are free to come up with new games and new ways of doing things. When I was young, this was a given, but with my daughter and her generation, not so much. I organized playdates, gave her Ipad, took her to playrooms. She was exposed to so many things that her focus would only jump from one thing to another. Left in a park, my daughter and her friends would come to me after 10 minutes and say “I’m bored”. I would give them a task: come up with 5 games in 3 minutes, and that would get things going.

-

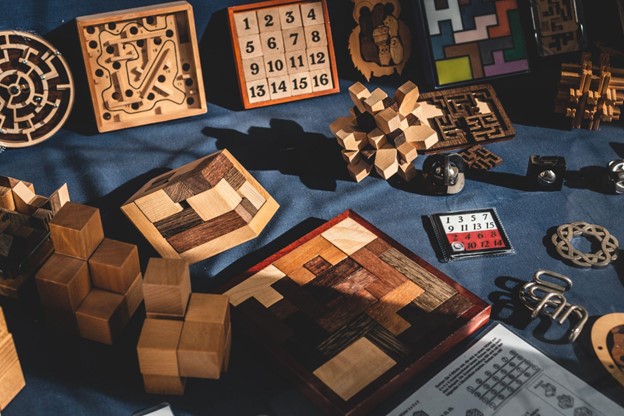

Choose books, cartoons, movies, toys, games, apps, etc. wisely.

The influence of the things above on children nowadays is immense. We definitely can’t hide from the development and lock our children into the last century, but we can be smart about it. Ask people to recommend movies, books, toys; check online for the highly-rated apps and games, read reviews whenever available.

The more general rule of thumb would be asking:

- Is this safe?

- Is this educational or just to pass time?

- What skills and values is this going to teach my child?

- Is there any violent content in it? (research confirmed over and over again that being exposed to violent TV, games, etc. provokes violence in children. They learn from the example.

Helping your children to develop critical thinking doesn’t take much resources or time, but it requires a different approach to parenting and a different mindset. You may try these tools one by one, giving a week to each, evaluate, maybe adapt and then decide whether to use or not. The way I see it, using these can make your parenting much more fun and you might learn a thing