A household with a working mom, not only challenges gender-based stereotypes, but also provides daughters with a role model they may best relate to. When it comes to boys, they are exposed to a household where everybody participates in domestic activities – not just the mother.

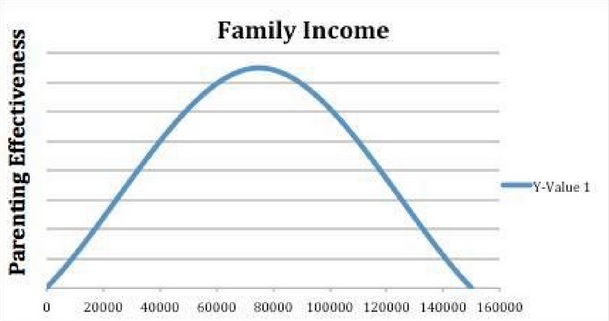

In his latest bestseller, David and Goliath: Misfits, Underdogs, and the Art of Battling Giants, Malcolm Gladwell presents a relationship between Family Income and Parenting Effectiveness. The assumption I had prior to reading this book, was that higher family income should be positively correlated with better parenting. Gladwell instead argues that the relationship between family income and parenting is instead an, „Inverted-U curve,“ and professes that there is no such thing as too much of a good thing. It is easy to rationalize why poorer parents are not the best parents because without an adequate supply of money, parents may not be able to provide a child with basic needs and services. However, in order to justify why the wealthiest parents are some of the poorest caretakers, one must acknowledge that although rich parents can afford many amenities, they may be too self-centered or career oriented to provide certain intangibles that are pertinent to good parenting.

As the median wage in the US per person is $26,695, if Gladwell’s estimates are correct then parenting effectiveness for the average American family can only be maximized when both parents are working. This may seem counter-intuitive to those who subscribe to the outdated notion that one of the fundamental roles for mothers is to stay-home in order to take care of children. A new Harvard Business School study discourages this ideology by providing ample evidence of the long-lasting, positive effects on children that result from mothers in the work-place.

The study, led by Professor Kathleen L. McGinn, has surveyed over 50,000 adults in 24 developed countries since 2002. The statistically significant results imply that compared to daughters of stay-home mothers, daughters of working mothers complete more years of education and are more likely to be employed in supervisory roles in the future. Regarding financial success, American daughters of working mother earn 23%, roughly $5,200, more than daughters of stay home mothers. Meanwhile, sons of working mothers are more conducive to doing household chores, spend more time in childcare, and are more likely to be married to women who work. The study found that, „sons of working moms spent seven and a half more hours a week on childcare and 25 more minutes on housework.“

The reasoning behind this logic is two-fold. A household with a working mother, not only challenges gender-based stereotypes, but also provides daughters with a role model they may best relate to. Children often look at their parents to understand how to behave, what activities to engage in, and what to believe. With a working mother who shares the responsibility of being the provider and also shares domestic responsibilities, sons and daughters realize that the idea of gender-specific roles is antiquated. The daughters of working mothers have the opportunity to observe, first-hand, the full range of possibilities that are available for women. Hence, they can confidently make the choice of being the women they want to be as opposed to the women they have to be.

The effect of role-modeling also occurs for sons. Although the default expectation for boys is to one day be the provider, by having a working mother, boys are exposed to a household where everybody participates in domestic activities – not just the mother. This imprints that work around the house is a shared responsibility, not a gender-specific obligation.

McGinn makes sure to not overlook the benefits of a stay-home mother and asserts that by no means is working motherhood morally superior. She claims, „It’s not that it’s right or wrong for women to work“¦It’s that there’s a set of options that seem fully available.“ The outdated concept is not that mothers have the option to stay-home but the idea that they have to stay home. McGinn believes that children can get adequate exposure to non-traditional gender role models, even if their mothers don’t work. She concludes that children of stay-home mothers that have friends whose moms work, „garner roughly the same benefits.“

It is important to understand that the implications by McGinn and Gladwell imply correlation, not causation. Households with two-working parents do tend to maximize parenting potential compared to their counterparts. However, a mother choosing to work does not necessarily result in a financially successful daughter or a more caring son. As parenting is very complex with numerous confounding variables, it is very possible, but not as likely, for the best parents to have a stay-home mother. The drive-home point of the study, as McGinn explains is that households with working mothers offers, „a set of alternatives around what’s appropriate behavior for boys and for girls, and that those alternatives aren’t constrained by really tight gender stereotypes.“