Boards of directors in charities around the world are looking for ways to replicate the success of the ice bucket challenge for their own charitable causes. But, before we go and copycat the phenomenon, let us evaluate it.

By the end of August, the ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) Association in the USA and its 38 chapters raised more than $100 million for patient care, advocacy and research to find a cure for ALS, better known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Fundraising for ALS charities was successful in other parts of the world as well, like the United Kingdom, Australia and Europe, albeit to a lesser degree.

Judged by any yardstick, the ice bucket challenge was a successful initiative which increased public awareness of ALS and raised a significant amount of much needed funds within a relatively short period of time, i.e. in a month. In other words, it is a fundraiser’s dream come true. It is no surprise that, since then, the boards of directors in charities around the world started looking for ways to replicate the success of the ice bucket challenge for their own causes and charities. But, before we go and copycat the phenomenon, let us evaluate it.

What is the ice bucket challenge?

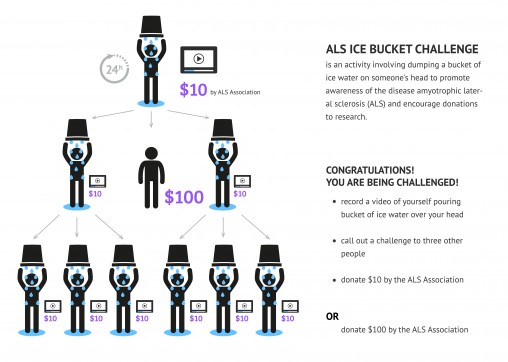

The ice bucket challenge involves filming the act of dumping cold water on a person’s head, preceded by nominating other individuals to do the same within 24 hours or make a financial donation to ALS charity. The video is then uploaded and promoted by individuals on social media, triggering a chain reaction of further challenges and donations.

What is the origin of it?

There were previous versions of this phenomenon, such as the ‘cold water challenge’ or the ‘polar plunge’ intended for fundraising for cancer research, but the ice bucket challenge became popular after the personalities of the golfing program Morning Drive performed a live, on-air, ice bucket challenge. Following this, golfer Chris Kennedy did the challenge and then challenged his cousin Jeanette Senerchia, whose husband suffered from ALS, thereby bringing the focus to ALS. Thereafter, a baseball player, Pete Frates began posting on twitter about his personal battle with ALS and about the challenge, resultantly encouraging other patients, their family members, sportspeople, celebrities, and politicians to do the challenge or donate to the cause.

Was it a formal campaign?

No, the challenge was neither formal nor planned fundraising campaign and it did not have a well-designed strategy with clear goals and targets. It was not initiated by the ALS association or the charities and it did not have any resources allocated for advertising and promotion.

What distinguishing factors made this challenge a success?

Potential donors needed to participate in a fun activity and publicize their participation. While the activity of dumping cold water on oneself was somewhat uncomfortable, the participants were rewarded by acknowledgement and praise for their efforts from their friends and peers; which proved to be a significant motivation to this generation of do-gooders who want to be ‘seen’ doing good. Secondly, the act of nominating others guaranteed the virality of the challenge and created a chain reaction of activities; a perfect result in any marketing strategy.

What did the ALS charities do to contribute to the challenge?

Once the challenge had caught the public attention, the ALS association and charities quickly capitalized on the increased attention and managed to adapt in order to continue gaining traction and keeping the momentum high by promoting the challenge through the Internet and social media. The lesson here was continual visibility on social media when such a phenomenon is taking place, how to do it, how to sustain it, with the overarching idea of using the social media as a valuable tool in attracting the current generation of potential donors.

Charities made it easy for members to donate by providing functional payment links and various payment options. The ALS charities also suggested an amount of $100 for a standard donation, even though any amount of donation was accepted. Many donors ended up donating the suggested amount, thinking that it was the minimum donation required. Additionally, in the later weeks, charities promoted that people could both take the challenge and donate. Charities made sure to promote on their websites and social media the films of local celebrities or groups who took the challenge and donated. Therefore, the ALS charities did not simply stand by and watch the phenomenon, but were active participants and enablers of the promotion and sustained the challenge during the intense period of its growth.

What were the failures?

While the challenge clearly raised awareness of ALS, it is unclear if the challenge managed to actually spread the important information about the disease. Simply counting the number of hits to the Wikipedia searching for ALS does not indicate that the public became more informed on the aspects of the disease; e.g. what are early onset symptoms, what is the challenge of living with ALS, where to seek care and support, or what type of care and support is even available? Relevant questions such as these were unfortunately not popularized by the challenge, therefore the opportunity for public education about the disease was predominantly lost.

Secondly, according to the ALS Association, the majority of donations came from new donors who numbered approximately 2.7 million at end August, which begs the question of whether these new donors will be repeat donors to the cause. This depends on the intentions of the donors who completed the challenge; did they do it because of peer pressure or did they do it due to a personal connection and belief in fighting the disease? It appears that this challenge was successful for the very reason of peer pressure through the dominant public presence in social media.

Should other charities imitate?

Charities can attempt to replicate, but not copycat, the ice bucket challenge by finding innovative and fun ways to promote their causes, utilizing social media, applying the participatory approach and the behavioural patterns of participants and donors, and revisiting their missions and visions in the light of learning from this challenge. Copycatting, on the other hand, would result in disastrous consequences for the charity in question, seeing that a failed public campaign can be a fundraiser’s nightmare and it may be many moons before the charity can rebuild its public image and support!