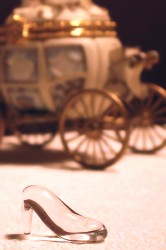

Fairytales. On them, I am an expert. The world’s best loved classic tales of love: “Cinderella”, “Beauty and the Beast”, “Sleeping Beauty”, “Snow White”, “The Frog-Prince”, I have them all, carefully shelved in the velvet library of my Greenwich Village apartment.

The very same romantic ideal – a yearning for love which culminates in happy ending- spans the spectrum of collective storytelling from Grimm Brothers to Walt Disney to Sex and the City.

The fairytale may be one of the most important cultural and social influences on children’s development. Who we become as adults, is largely influenced by the stories we were told. Though we teach young boys and girls to believe in happy endings, the question remains: how much faith is sufficient to sustain the fairytale’s suggested belief that someday, somewhere, a better world awaits? In the age of broken dreams and brush reality and so many examples of people who did not make it after all, what is our responsibility, if any, in telling a child what’s possible? What does the fairytale stand for? What can we learn from it?

The Fairy Grandmother(Cinderella):

Even miracles take a little time.

Happily Ever After: A Postmodern Fixation or Reality?

On April 29th 2011, the whole world stopped to witness the fairytale unfolding in front of their eyes: the wedding of Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, and Catherine Middleton. The bride, the cake, the Household Cavalry and the Duke, made the whole world stop in a breathless moment. The Royal wedding turned into a public holiday, a global celebration of romantic love. Sometimes, the real life writes the best copy.

On April 29th 2011, the whole world stopped to witness the fairytale unfolding in front of their eyes: the wedding of Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, and Catherine Middleton. The bride, the cake, the Household Cavalry and the Duke, made the whole world stop in a breathless moment. The Royal wedding turned into a public holiday, a global celebration of romantic love. Sometimes, the real life writes the best copy.

However, romantic expectations of a contemporary woman who once-upon-a-time was a young girl dreaming of a knight in shining armor, not always end up in happy ending. Young Fiona in Shrek, the musical, ironically says: “A torturous existence, I don’t remember this part!”

One only needs to look at the feminist project focused around the critique against the model of a virtuous girl who’s forever waiting for a Prince Charming to come to her rescue and to feel like giving false promises to a child.

From a feminist criticism of the gender stereotype to a traditional interpretation of a moral virtue, what is it we can make of the magical storytelling? If we were to tell the children not to believe in happy endings as ways of protecting them from potential disappointments, wouldn’t we be crushing their dreams based on no evidence but our fearful projections?

Lesson in Faith or Reality Invented?

What fairytale narrative provides is a magical experience for a child. It is one of the primary sources of meaning to child’s life and understanding of human behavior. Fairytales aim to project a vision of a better world. But what happens when life throws you a curve ball? What happens when great expectations turn out not to be so great? “Cut the villains, cut the vamping/Cut this fairytale/Cut the peril and the pitfalls/Cut the puppet and the whale/Cut the monsters, cut the curses/Keep the intro, cut the verses/And the waiting, the waiting, the waiting, the waiting/ The waiting!” screams Fiona frustrated of waiting for her true love in Shrek, the musical.

Exposing children to fairytales in which the cruel and frightening scenes are edited or omitted would mean exposing them to only one side of reality. Lucia O., the main protagonist of my novel Letters to the Wind, in her search for “happily ever after”, mistakenly chooses a Dark Prince figure whose brusque and cruel treatment drives her deeper into despair. However, Lucia’s O. journey is also largely about self-reinvention and how despite love’s power to break her down again and again, she remains determined to piece her story back together and become the hero of her own narrative. And that’s what fairytale is all about.

Exposing children to fairytales in which the cruel and frightening scenes are edited or omitted would mean exposing them to only one side of reality. Lucia O., the main protagonist of my novel Letters to the Wind, in her search for “happily ever after”, mistakenly chooses a Dark Prince figure whose brusque and cruel treatment drives her deeper into despair. However, Lucia’s O. journey is also largely about self-reinvention and how despite love’s power to break her down again and again, she remains determined to piece her story back together and become the hero of her own narrative. And that’s what fairytale is all about.

In no success story, even the most fairylike, from Steve Jobs to Novak Djokovic, did the hero manage to escape dealing with obstacles on his way from rags-to-riches. Challenges the hero is exposed to offer a toolkit for riding the wave of life. Fairytales offer ways of resolving a stranglehold situation that at times may seem insurmountable and can inspire child to look beyond the limiting circumstances.

Thus, fairytales are nothing but lessons in faith. Faith, that everything is possible.

After winning Wimbledon and becoming the world’s No.1, Novak Djokovic said:

There’s no end in dreaming: never give up on your dreams.

So take your chances. Become a hero of your own narrative. Maybe life is a fairytale, after all.

With Love,

Ksenija Pavlovic